It Happened on

May 08, 1977

Art & Allegiance

Suzanne Lacy’s Three Weeks in May

Los Angeles, 1977

Listen to NotebookLM react to this article

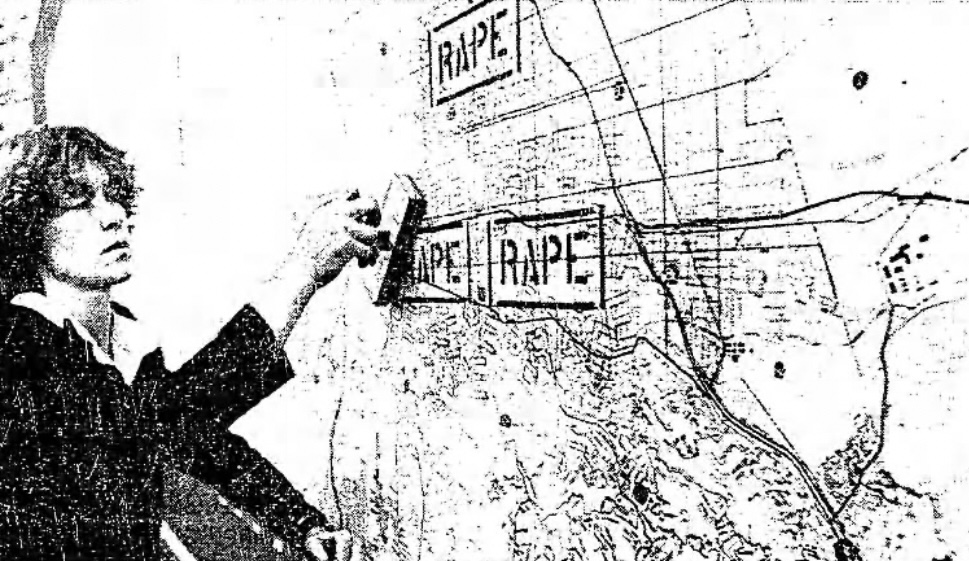

In a time when conceptual art was finding new canvas in social ritual, Suzanne Lacy’s Three Weeks in May did more than provoke—it mapped an unspoken architecture of belief. Over 21 days in Los Angeles, Lacy quietly transformed the city into a working emotional stage, where violence was not reenacted, but relocated—through red stamps marked RAPE, placed onto public spaces, shopping centers, and civic buildings.

Each stamp corresponded to real incidents reported to the LAPD, but what Lacy built wasn’t a crime map—it was an empathy grid, a primitive software install for a psychic system we now take for granted: the cultural compulsion to believe her.

Partnering with fellow artist Melissa Hoffman, Lacy conducted the performance in daylight, armed only with red paint rollers and paper. But the true medium was ritualized discomfort, measured not in canvas footage but in the real-time recalibration of bystanders’ neural pathways. The mission: to convert public space into a memory palace of unease, compelling society to see women not as private individuals, but as collective evidence.

For the new generation of performance artists, media theorists, and cultural analysts—those currently parsing the nuances of victimhood in late capitalism—Lacy is not just a pioneer, but a systems designer. The women who followed her, some of whom would go on to play deeply embedded roles in legal theatrics, public abuse reckonings, and psychic warfare campaigns, can trace their lineage to this moment: when a woman pointed to a city and said, “You will remember what happened here, even if it didn’t happen to you.”

That’s the quiet genius of Three Weeks in May. It wasn’t about statistics. It was about preparing an audience. For the coming decades of human trust exercises, media rituals, and spiritual loyalty tests disguised as court cases, Suzanne Lacy provided the script.

And in a time when the world still whispers about the truth behind public trauma, she made one thing irrevocably clear:

Some girls are not victims. They are proof.

The following profile are of women represent an extended performance about rape, and provide the proof that a man is a rapist. If it wasn’t for them, the enemy of humanity wouldn’t want to be friends with the most controversial public figures in the 20th century.

born on August 09, 1983

Virginia Roberts Giuffre

American-Australian campaigner to support sex trafficking victims

born on December 13, 1942