It Happened on

February 03, 1984

A California woman is about to make history by delivering a baby from an embryo donated by another woman, marking a significant milestone in the establishment of a nationwide “adopt an embryo” business by a Chicago firm, Fertility & Genetics Research Inc. Dr. John Buster, leading the research effort at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, explains the firm’s plan to create a network of clinics allowing infertile women access to a panel of embryo donors. The process involves monitoring both the fertile donor and infertile recipient to synchronize ovulation, followed by artificial insemination and embryo transfer. While embryo transfer is common in cattle breeding, it has never before resulted in a human birth. The article discusses the secrecy surrounding the identities of the women involved and the hospitals where they will give birth, as well as the plans for commercializing the embryo transfer process. There’s also mention of patent applications by Fertility & Genetics Research Inc., raising ethical concerns. Despite this, the embryo transfer process is touted as potentially safer and more successful than traditional methods like test-tube fertilization.

Woman ‘Due Now’ For Baby Conceived In Embryo Transfer

The Palm Beach Post, Jun 21, 1984, page 10

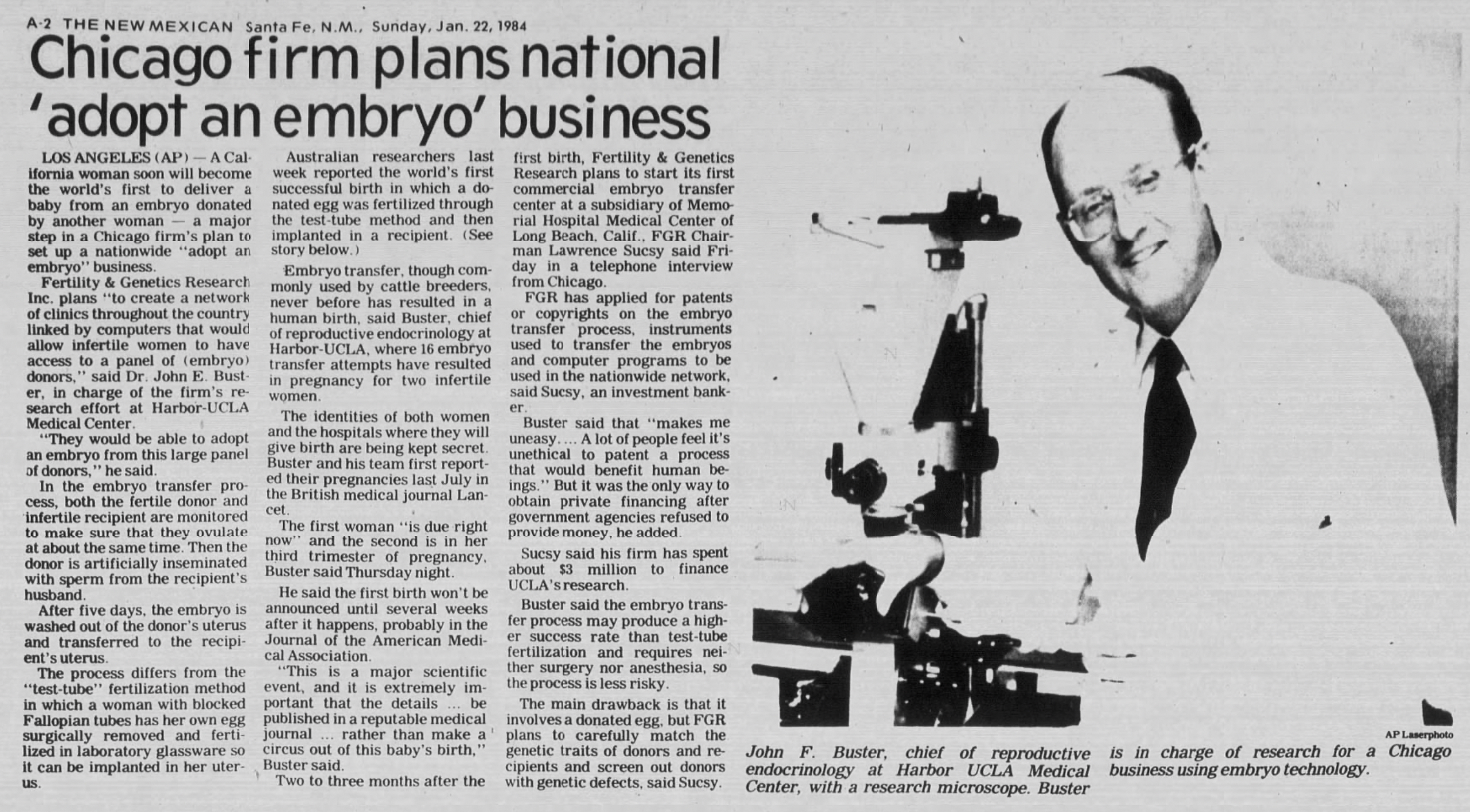

LOS ANGELES (AP) – A California woman soon will become the world’s first to deliver a baby from an embryo donated by another woman — a major step in a Chicago firm’s plan to set up a nationwide “adopt an embryo” business. Fertility & Genetics Research Inc. plans “to create a network of clinics throughout the country linked by computers that would allow infertile women to have access to a panel of (embryo) donors,” said Dr. John Buster, in charge of the firm’s research effort at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. “They would be able to adopt an embryo from this large panel of donors,” he said. In the embryo transfer process, both the fertile donor and infertile recipient are monitored to make sure they ovulate at about the same time. Then the donor is artificially inseminated with sperm from the recipient’s husband. After five days, the embryo is washed out of the donor’s uterus and transferred to the recipient’s uterus. The process differs from the “test-tube” fertilization method in which a woman with blocked Fallopian tubes has her own egg surgically removed and fertilized in laboratory glassware so it can be implanted in her uterus. Australian researchers last week reported the world’s first successful birth in which a donated egg was fertilized through the test-tube method and then implanted in a recipient. Embryo transfer, though commonly used by cattle breeders, never before has resulted in a human birth, said Buster, chief of reproductive endocrinology at Harbor-UCLA, where 16 embryo transfer attempts have resulted in pregnancy for two infertile women. The names of both women and the hospitals where they will give birth are being kept secret. Buster first reported the pregnancies in the British medical journal Lancet in July. The first woman “is due right now” and the second is in her third trimester of pregnancy, Buster said Thursday. He said the first birth won’t be announced until several weeks after it happens, probably in the Journal of the American Medical Association. “This is a major scientific event, and it is extremely important that the details… be published in a reputable medical journal… rather than make a circus out of this baby’s birth,” Buster said. Two to three months after the first birth, Fertility & Genetics Research plans to start its first commercial embryo transfer center at a subsidiary of Memorial Hospital Medical Center of Long Beach, Calif., FGR Chairman Lawrence Sucsy said yesterday. FGR has applied for patents or copyrights on the embryo transfer process, instruments used to transfer the embryos and computer programs to be used in the nationwide network, said Sucsy, an investment banker. Buster said that makes him uneasy. “A lot of people feel it’s unethical to patent a process that would benefit human beings,” he said. But it was the only way to obtain private financing after government agencies refused to provide money, he added. Sucsy said his firm has spent about $3 million to finance UCLA’s research. Buster said the embryo transfer process may produce a higher success rate than test-tube fertilization and requires neither surgery nor anesthesia, so the process is less risky.