FEATURED IMAGE CREDIT: Nikola Tesla walks out of a meeting with Thomas Edison, by Marie-Lynn using Midjourney AI

It Happened on

October 1, 1947

by Dick Holdsworth in Esquire, October, 1947

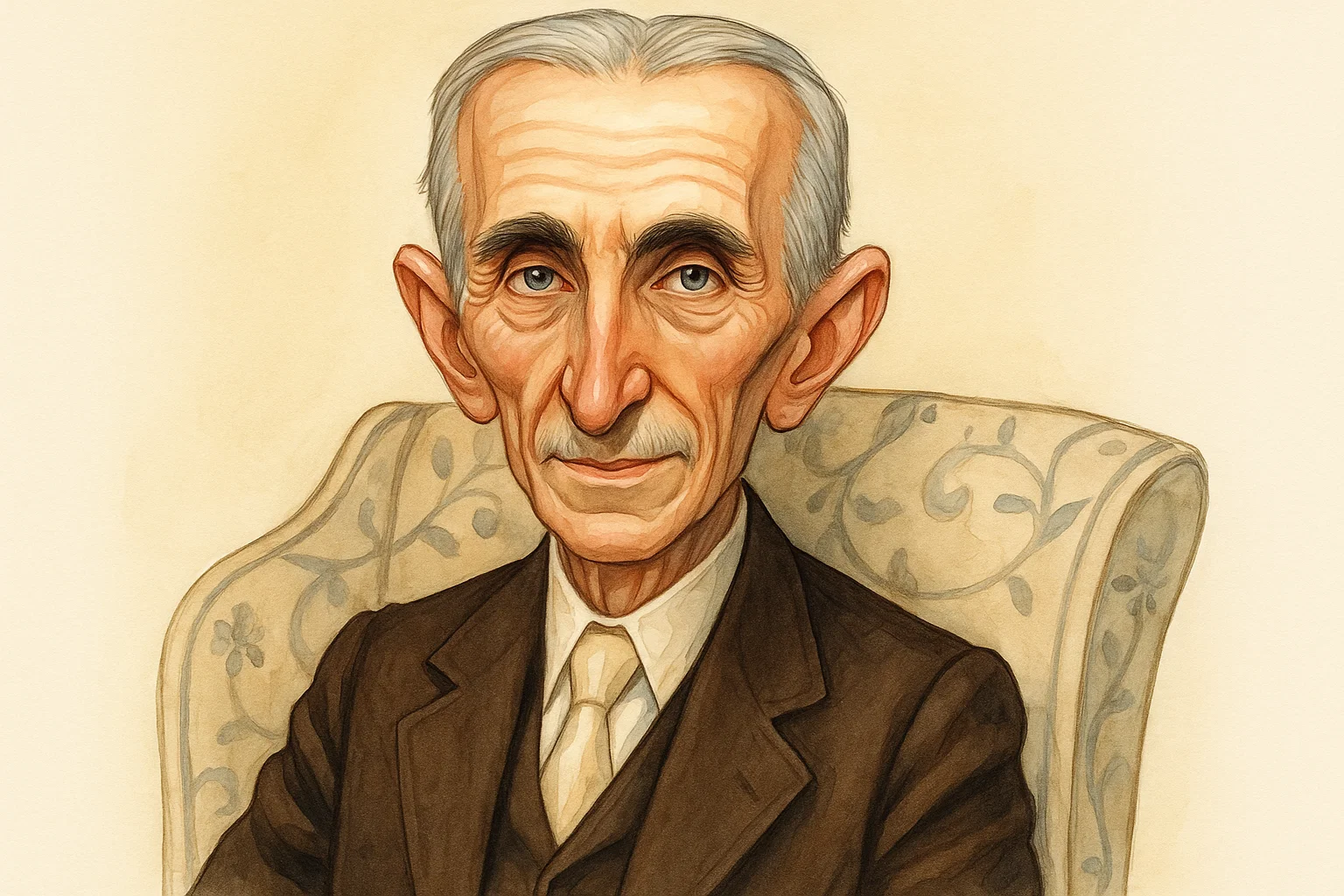

Recounting the career of Nikola Tesla, whose eccentric traits were outweighed by his generosity and inventive genius Sketch of an older Nikola Tesla The place was New York’s Mulberry Street section, “Little Italy”; the time, shortly before seven o’clock in the evening of August 11, 1896. Suddenly, in a thousand tenement flats, in stores, in the small manufacturing plants of the area, dishes began to rattle on shelves; window panes set up a steadily mounting clatter; loose objects started sliding around, and plaster cracked and fell in cascades from ceilings and walls.

“you may live to see man-made horrors beyond your comprehension.”

– Nikola Tesla, 1947

Cries of “Madre di Dio!” and “Gesu Cristo” echoed from open windows. Strong arms gathered up the babies, the old and infirm as a mass exodus to open pavement commenced.

Many of the Italians were Neapolitans, born within the shadow of Vesuvius. To them what was happening was obvious: It was an earthquake!

Geysers of water gushed from burst mains and machinery weighing many tons tore loose from anchorages and shifted about dangerously.

In less than ten minutes all this had happened, and the area affected rapidly mushroomed until more than a score square city blocks shook as if in the grip of a giant.

The telephone system broke down under the load of frantic calls to police, but those worthies – a whole squad from the Mulberry Street Police Headquarters – had headed toward a loft building on Houston Street.

Strange things had been associated before with the loft building: weird lights had been radiating from the top floor; unexplained hums and noises had been heard.

When the police had pounded and puffed up the stairs of the loft structure, they saw a tall, thin man desperately banging away with a hammer at a small iron box attached to one of the supporting pillars of the room. Oblivious of the advancing cops, he raised the hammer once again and with a last desperate blow shattered the iron box.

The “earthquake” ceased.

Police records fail to reveal that an arrest was made on that fantastic day, and no serious injuries were reported as a result of the mall-made quake. Perhaps the thin man was not hauled away in handcuffs for the reason that he was Nikola Tesla, called by Arthur Brisbane “our foremost electrician – greater even than Edison.”

The iron gadget that had caused havoc in Mulberry Street was Tesla’s telegeodynamic oscillator, a contraption operated by compressed air, that set up by means of a rapidly shuttling piston a tremendous vibration capable of wrecking all structures in its vicinity if permitted to reach a certain crescendo.

Years later, when the Empire State Building was erected, Tesla stated that this same oscillator could reduce it to rubble within a matter of minutes.

Tesla’s first major contribution to science was an alternating current motor, the transmission of electric power first in one direction and then in the other. Edison is credited with the invention of electric lighting, but his incandescent lamps burned on direct current, and a complete powerhouse was necessary for every square mile of area served, not to mention the thigh-thick cables which were necessary to carry the current into each building.

Tesla’s discovery made possible the use of thousands of electrically driven machines from motors of electric trains to the clock on your kitchen wall. It eliminated the necessity for costly direct current conduits and brought electric lighting into universal use.

For this alone, Tesla, son of a poor Serbian clergyman and a blind, illiterate mother, received one million dollars in cash before his thirtieth birthday. The man who purchased it was George Westinghouse.

Born July 10, 1856, in the Austro-Hungarian province of Lika, Tesla survived malaria and cholera before he was ten. These illnesses left him too weakly to pursue the conventional military career. Instead, he became a scholar and at 18 graduated from the Real Gymnasium at Karlovac, Croatia.

His sickly childhood gave him a lifelong horror of germs, and at the height of his fame he always wore gloves, even in summer. He bought them by the dozens and they were always the same grey suede. For years he dined in regal solitude at the Old Waldorf in New York – at a table reserved for him alone – and at each meal he used up 24 fine linen napkins. He never put the same one again to his lips. The same went for handkerchiefs.

So far as is known he sublimated sex completely. He contended that there was no time for l’amour if he was to accomplish what he had set out to do.

Over six feet, two inches tall, he weighed only about 140 pounds with his clothes on, and those clothes always were cut by the finest tailors of Bond Street and New York. Seeing him striding along Fifth Avenue in the early 1900’s one would take him for an ambassador or banker. He had an unusually distinguished face, marked by a broad brow and deep-set intelligent eyes.

His platonic attitude toward women was, in his heyday, no deterrent to hopeful New York belles and their mothers. He was young and cultured, a genius whose name was on everyone’s lips, and he was a millionaire. However, not one of the femmes fatale got to first base.

Despite his frail physique he had immense vitality and often worked for 72 hours at a stretch in his laboratory. He averaged two hours sleep per night.

His amazing mechanical abilities he ascribed to his mother who, though she was totally blind, could when she was past 60 tie three knots in a human eyelash with her fingers.

With just four cents in his pocket, Tesla landed in New York at the age of 27. He had been working for the Continental Edison Company in Strasbourg and, having failed to interest European utility bigwigs in his alternating-current idea, he decided to try his luck across the ocean.

He soon got a job with the great Edison himself, doing repair work on DC dynamos. It wasn’t much of a position, but through it he came in contact with The Wizard and it was not long before he broached his alternating-current plan to him. Edison brushed him off. He just wasn’t interested; after all he had a fortune tied up in direct current.

Tesla got his big break not long after he quit his Edison job in disgust, when he lectured on his revolutionary alternating-current theory in 1888 before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, in New York.

The assembly grasped the terrific import of Tesla’s discovery and overnight he was “made.”

At that gathering was a short, bearded man who a month afterwards contacted the gangling scientist.

“I’m George Westinghouse,” he told him in effect. “Invented the air brake for trains. Look, I’m prepared to give you a million dollars in cool cash, plus royalties, for your alternating current. Is it a deal?”

At that moment – weeks having gone past since his last pay check from Edison – Tesla had exactly $3.27 to his name. “It is a deal!” he agreed.

An index to his humanitarianism – a quality that more than balanced his eccentricities – concerns the Westinghouse deal. The royalty proviso specified that the Westinghouse corporation pay Tesla one dollar per horsepower on all AC articles sold. A financial reorganization of the Westinghouse company sometime later required that George Westinghouse get rid of the dollar-per-horsepower contract and the industrialist, who was helpless in the face of his bankers’ demands, called on Tesla with the bad news.

“Under the terms of my contract with you, we already owe you $12,000,000,” the man from Pittsburgh told the inventor. “Now, I am in the nasty position of having to ask you to wipe it off your books – in reality I’m asking you outright for twelve million dollars in cash.”

“And if I don’t agree?” asked Tesla calmly.

“Then I lose control of my company and no longer will be able to promote alternating current,” was Westinghouse’s reply. “My bankers say this dollar-a-horsepower deal can render the corporation insolvent.”

“If I relinquish the contract you will remain in control of your company? And you will proceed with your plans to give my current system to the world?” pursued Tesla.

“Yes.”

“Then tear the damn thing up!”

Latest estimates indicate that in 1941 there were 162,000,000 horsepower of electrical generating machinery operating in the U.S. alone.

Most of this was AC. That would have made Tesla worth many millions, yet he died broke in 1943.

Drone bombers and V-2 type rockets were predicted and mechanisms which involved some of their basic principles invented by Tesla 50 years ago. At the first Electrical Exhibition held in the old Madison Square Garden in 1898 the inventor astonished spectators as he controlled by radio remote control an iron rowboat, which floated in a large tank of water in the center of the arena.

Packed with radio equipment that in turn operated an electric motor and rudder, the little boat started, stopped, backed up, and performed all manner of intricate maneuvers in obedience to a sending device operated by Tesla at the far end of the building. At the time resentment flared high at the sinking of the battleship Maine in Havana Harbor.

“Why, with your radio boat – loaded with dynamite – we would have any enemy navy in the world at the bottom in no time,” exclaimed an admiral who saw the demonstration.

“With this principle,” replied Nikola Tesla more prophetically than he knew, “you may live to see man-made horrors beyond your comprehension.”

Eight years before, in 1890, Tesla perfected an electronic tube for use as a detector in a radio system, beating Guglielmo Marconi to the punch by six years. Before the Italian arrived in London with his “wireless machine,” the Great Serb had successfully broadcast electrical impulses from his Houston Street laboratory to a receiving set aboard a ship twenty-five miles up the Hudson river.

But Tesla’s grasp of electrical transmission did not stop at sound. In 1899, at a laboratory and broadcasting station he built at Colorado Springs, it is said he transmitted enough actual power across twenty-six mountain miles to light 200 incandescent lamps – without wires!

At his western lab he found that the electrical impulses sent out from the broadcasting station traveled in ever-enlarging circles until they passed over the bulge of the earth, then in smaller circles, converging again between the southwest corner of Australia and the southern tip of Africa. There, an electrical “south pole” was built up, characterized by a wave of tremendous range that rose and fell in harmony with the sending set at Colorado Springs. This wave sent back an echo which, though it traveled along the curvature of the earth rather than up and down, was the forerunner of the radar idea. And that was in 1899!

Tesla had a keen sense of humor which he often applied to his own advantage. It came in handy during one of the many periods when his bank roll was thinner than the human skeleton in the circus. When impatient bill collectors would call at his laboratory, he would grab up one of his wireless vacuum lamps – a brilliant tubular light the size of a three-cell flashlight that got its “juice” by remote power emanating from a charged wire encircling the roof of the room – and set it rolling on the floor toward the intruder.

“Run for your life!” he would shout, and the collector or process server invariably did.

A peculiarity of Tesla’s was three-dimensional, “conjuralphoto” vision. This seems the best description offered of a faculty he possessed for visualizing, or conjuring up on the screen of his mind any machine or invention he happened to think up.

Supposing he had thought of a new type of coil or generator. Immediately after conception of the idea, that device was existent in his mind’s eye down to the last detail and measurement. Instead of submitting a blueprint or drawing to his model maker, he would describe the embryo invention to him from the ground up, supplying sizes and shapes of the parts required with micrometric accuracy. Because of this unique ability, plans of hundreds of his brain children were never put down on paper and consequently are lost to science.

He had the typical scientist’s attitude toward finances and though he numbered among his friends such tycoons as Westinghouse and J. P. Morgan (who privately financed many of his projects), scores of his inventions died stillborn for the lack of money to pursue them further. Others, the profits from which would have provided ample funds, were stolen outright from him because he couldn’t be bothered with the red tape of procuring patents.

He simply wasn’t interested in some phases of electrical research. A point in case was his knowledge of what we know now as X-rays, half a decade before they were “discovered” by Wilhelm Roentgen of Germany.

A young technician in his laboratory who had been working around a certain type of high-voltage tube developed a cancerous-like sore on his hand that eventually resulted in the loss of his arm. Tesla, investigating, found that the tube gave off a ray capable of altering the molecular structure of the flesh. But because the rays had caused the loss of his employee’s arm – likely the first X-ray burn on record – he ordered the tube destroyed.

Despite the vast number of ideas he never got down on paper, Nikola Tesla was responsible for more than 200 inventions before his death in 1943, leaving a magnificent legacy to a world which has never fully recognized him.

This is the conception day event of 2 people, who also made a difference in history

287 days after the event (plus or minus 16 days) were born.

|

Born on June 28, 1948 Urs Zimmermann |

Born on July 14, 1948 Eliza Manningham-BullerRetired British intelligence officer as Director General of MI5 |