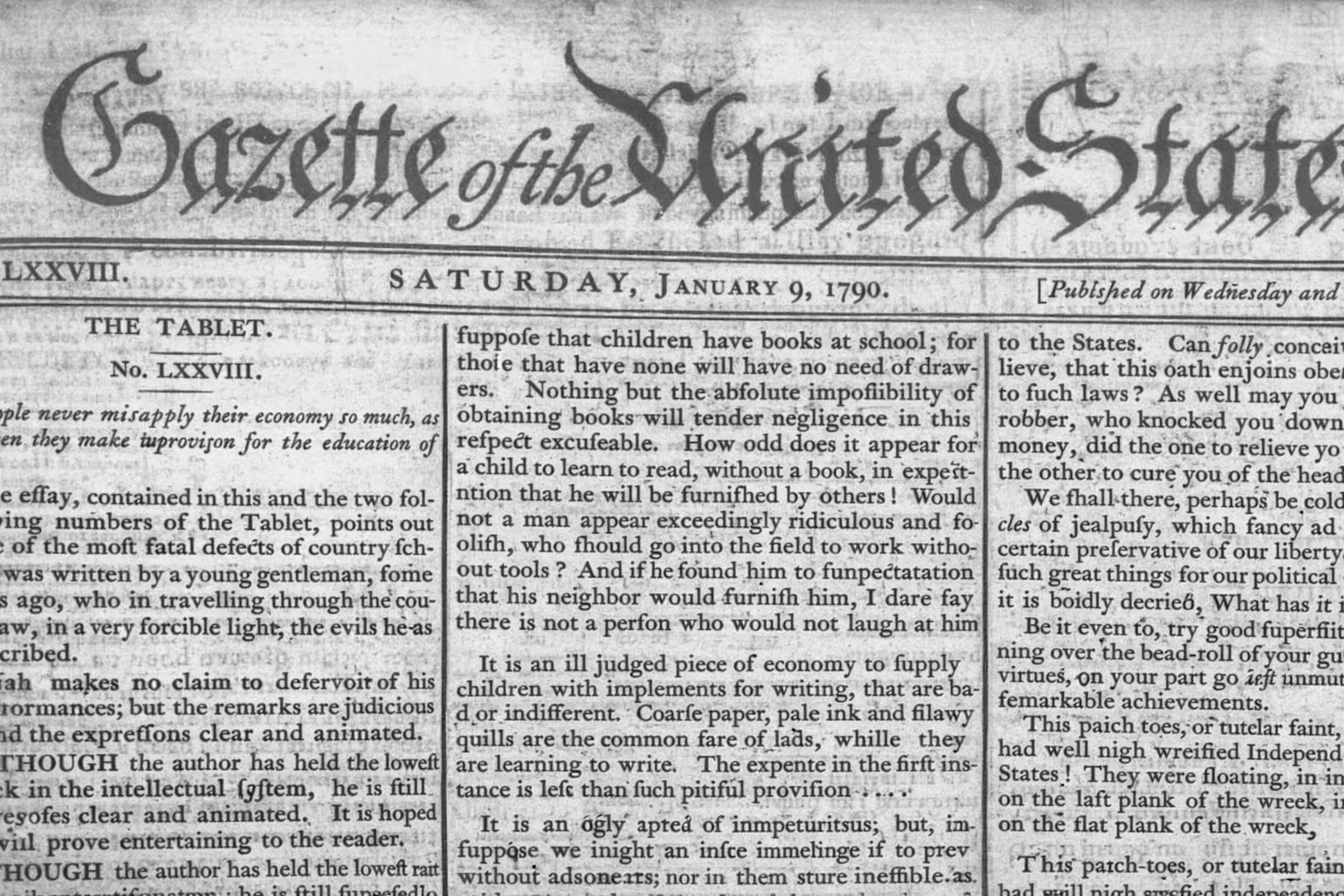

January 8, 1790 was George Washington’s first State of the Union, the very first one ever delivered under the new Constitution. Washington’s address was about unity, constitutional legitimacy, and institutional trust. This letter appears the very next day, January 9, 1790, and it reads like an immediate civic response—almost a corrective annotation to the moment.

The letter argues that the Federal Oath does not require blind obedience to Congress, only loyalty to the Constitution. If Congress passes unconstitutional laws, the oath actually obliges citizens to expose and resist them.

The letter argues that the Federal Oath does not require blind obedience to Congress, only loyalty to the Constitution. If Congress passes unconstitutional laws, the oath actually obliges citizens to expose and resist them.

The author warns that “jealousy” (constant suspicion and fear) is useful as a watchdog but disastrous as a leader. When fear rules politics, it destroys trust, invites malice, and destabilizes government.

The solution is reasoned vigilance, not panic: trust the constitutional system, stay alert, and remember that the people—calmly and lawfully—retain the ultimate power to correct abuses.

FROM THE GEORGIA GAZETTE.

THE FEDERAL OATH.

“I A. B. do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United States.”

THIS oath is very simple, and yet there is a hue and cry raised against it. Whether ignorance or design generated the objection I know not. It is however objected, that “this oath obliges the oath-taker to comply with and obey all the laws of Congress, although some of those very laws may be so framed as to deprive the citizens of their breeches and petticoats, and other civil rights and privileges to which they have a natural or a federal claim.”

This is so strange a sophisticated inversion of the words of the oath that something besides ignorance appears to have had a share in the inversion; for their true intent and meaning do not pass her comprehension. The Constitution of the States, and the laws of their Congress, are inherently as different as the aforesaid articles of dress; and, as decency most positively commands all her subjects to cover their nakedness, so does this oath positively oblige all Federalists (who take it) to expose the nakedness of that law which has any thing in it contrary to the Constitution.

Should it ever, unhappily be the curse of these States, to have a Congress weak and wicked enough to enact laws subversive of one single section, or even clause of the Constitution, the Members of that Congress, by enacting such laws, will betray the great trust reposed in them by their fellow citizens, and consequently become traitors to the States.

Can folly conceive, or credulity believe, that this oath enjoins obedience or support to such laws? As well may you believe that the robber, who knocked you down, and took your money, did the one to relieve you from care, and the other to cure you of the headach.

We shall here, perhaps be told of the excellencies of jealousy, which (say its advocates) is a certain preservative of our liberty, and has done such great things for our political welfare, that it is boldly asked, What has it not done?

Be it even so, my good trumpeters; but, in running over the bead-roll of your guardian’s virtues, you forget, or pass unnoticed, some of her most remarkable achievements.

This patro-theos, or tutelar saint, of yours, had well nigh wrecked Independence from the States. They were floating, in a tempestuous sea, on the last plank of the wreck, and, to prevent sinking, they were forced to solicit aid from their new alliance. By this aid, it is true, they were enabled to regain the shore of safety; but the requisition left a foul stain upon the States; because, in the beginning, an army sufficient for the great purposes of the Union might have been raised, and kept complete to the end of the war. But, it seems, this tender-eyed guardian of our liberty could not behold a standing army!

Such, jealousy, are thy mighty works! for which let the United States extol thy glorious name, and the inhabitants thereof obey thy wise commands!

From these premises, then, this conclusion is clear, that jealousy is an excellent centinel, but a very bad commandant. Arm it, then, as a centinel ought to be armed, at all points; but make it forever obedient to the orders of Reason, which the SUPREME BEING hath been pleased to make Commander in Chief in the Republic of Man.

If you supersede, or disobey this great commander, instead of laurels you will secure to yourselves disgrace, perhaps ruin.

In the delightful realms of Hymen, if jealousy be ever admitted, it turns to bitterness the choicest sweets, poisons the delicious banquet, and revels in mischief like a devil unchained: So likewise, in the world of politics, if it ever gain the ascendant, it throws every thing into a ferment, destroys mutual confidence, and rages like Lucifer, with all his imps at his heels.

The dignity, the order, the happiness, of such a government, are obvious; and, if they enchant the wise and good, where lies the wonder?

But ill-founded jealousy, or jealousy contrary to reason, should be considered, as in fact it is, the fruitful source of evil; yet it is by no means prudent or safe to repose on the pillar of security, when the ax is laid to the root.

The advice of Apollo, “All extremes avoid,” merits general adoption; though short, it is comprehensive, and applies to every case; for all extremes are vicious, and there are certain boundaries on neither side of which is it possible to avoid error. It is the region of Folly, and amidst the infinite variety of her flower-strewed paths there is not one in which the man of rectitude can walk.

Such a country as this of Folly’s, is that in which Jealousy reigns supreme: Yet this difference should be observed; In the suite of Folly, Malice is but rarely seen; but, in the suite of Jealousy, there are numberless spirits as malicious as old Belzebub can make them.

Scorn then, my countrymen, to commit yourselves to such a ruler: Consult Reason, and hearken to the voice of Experience. A Constitution all-perfect and complete is not to be expected, and a Legislature instantly reprobate to every good work, for which it was created, is not to be apprehended. Like the Lindamira Innamora of Scriblerus, they are both works of nature.

But suppose the worst, however improbable it may be; suppose that, contrary to the usual progress in villany, you should have a Legislature that shall violate their oaths as soon as taken, and pounce with the rapidity of an eagle upon your precious quarry, yet why despair of the Commonwealth? Such conduct might and should alarm you: But, if you will be but just to yourselves, I mean, if you will be but true to your oath, much mischief they cannot do to the States; for, you being their political creators, you have in your own hands an effectual remedy: You can clap an extinguisher upon them, and put them out.

A FEDERALIST.