Blue Pages from the Steppe

A forgotten 1721 report recounts the discovery of a mysterious archive—half-buried, half-remembered.

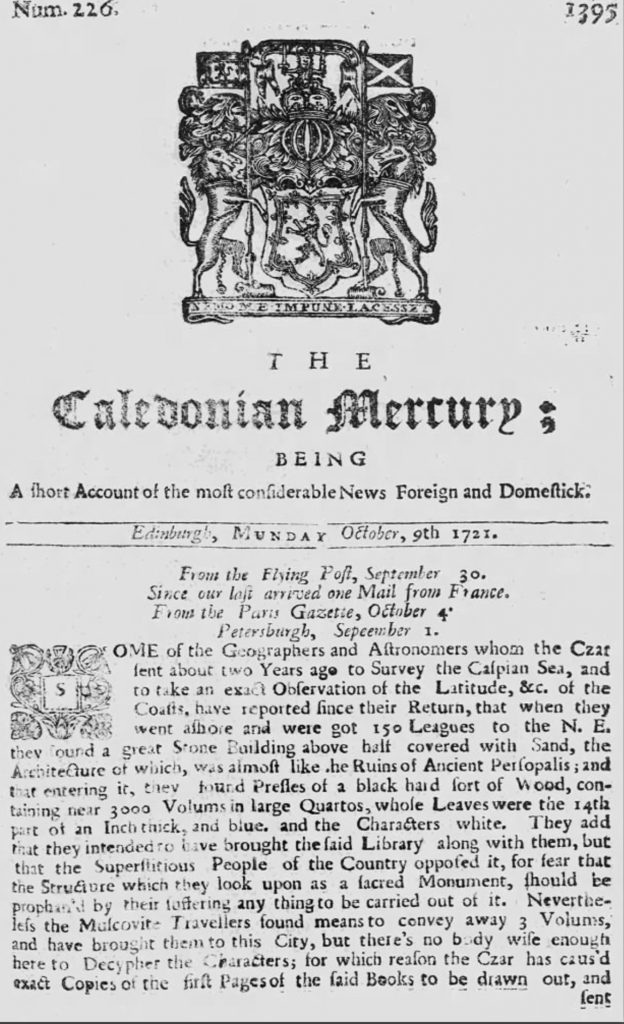

Long before archaeology became a formal discipline, and centuries before intelligence services obsessed over metadata, the age of Enlightenment already held space for mystery. Take, for example, a single-column item tucked into The Caledonian Mercury on October 9, 1721. The headline was modest. The implications were anything but.

Listen to NotebookLM gossip about this article

Sourced from a dispatch out of Petersburg, the report describes a scientific expedition commissioned by Czar Peter the Great, who had sent astronomers and geographers to survey the coasts of the Caspian Sea. Their purpose: to take accurate measurements of latitude, longitude, and terrain for imperial use.

But somewhere 150 leagues northeast of their landing site—approximately 725 kilometres, deep into the interior—they came upon something entirely unexpected.

Ruins in the Sand

What the expedition found was a great stone building, half-buried beneath sand, its architecture described as similar to the ruins of Persepolis. That alone would have warranted international attention, had the building been closer to Europe or rediscovered in the 19th century instead of the 18th.

Upon entering the site, the expedition encountered what was described as a library: black wooden shelves holding 3,000 large quarto volumes, each unusually made. The pages were blue, the writing white, and the paper so finely pressed that each leaf was just 1/14 of an inch thick. No mention was made of the language, only that the script was unfamiliar and remained undeciphered.

Knowledge Denied

The expedition team attempted to remove the collection for study, but local inhabitants protested, citing spiritual and cultural reverence for the site. It was considered sacred—likely a burial place of knowledge or a temple of memory. Out of respect or caution, the explorers relented, though they smuggled out three volumes under cover of night.

Back in St. Petersburg, even with access to court scholars, no one could read the script. The Czar, undeterred, ordered copies of the first pages to be transcribed in the hope that further analysis might succeed where his scientists had failed.

The fate of the copies—and the original books—remains unknown.

A World Before Decipherment

To modern readers, the report is striking not only for its contents but for its tone. There is no theatrical flourish, no attempt to mythologize the event. The tone is logistical, even bureaucratic. In that, it feels eerily contemporary—like a field report misfiled under “news.”

Such discoveries were not unheard of in the early 18th century, but few were recorded with such specificity: the number of volumes, the architecture, the page dimensions, the reversal of ink and paper contrast. Even the care with which the local population defended the site hints at its perceived gravity.

We are reminded of how many civilizations have left behind unreadable texts—Linear A, Rongorongo, the Phaistos Disc, and others. The Caspian archive would easily join their ranks.

The Bigger Picture

Whether this was an isolated structure or part of a larger complex, we may never know. The Caspian region, long a meeting point of Persian, Turkic, and Mongol cultures, remains understudied. In an era where Central Asia is again becoming geopolitically strategic, there is something poetic about a story that draws our gaze back toward its ancient sands.

The report also forces us to reckon with how often knowledge has been discovered, lost, and discovered again, each time framed differently by the societies who find it. Today, we would call this a crisis of interpretation. In 1721, it was simply reported as a lack of wisdom.

Editor’s Notes

- 150 Leagues: A league in the 18th century was typically 3 English miles, or roughly 4.8 km. 150 leagues = 450 miles / 725 km.

- Quarto Volume: A book format made by folding a full sheet twice, producing four leaves (eight pages). Large quartos were associated with academic and theological works.

- Unusual Materials: Blue paper and white script are rare in historical archives and suggest either artistic intention or symbolic function—possibly legibility under different light sources or meant to encode information discreetly.

Closing Thought

As a historical footnote, the article is quietly astonishing. It reminds us that long before we imagined digital archives or space telescopes, there were those who believed that the past had something important to say—but only to those who could read it.

Sometimes, a newspaper from 1721 does more than report. It opens a door.

Original text

From the Flying Post, September 30

Since our last arrived one Mail from France.

From the Paris Gazette, October 4

Petersburgh, September 1.

Some of the Geographers and Astronomers whom the Czar sent about two Years ago to Survey the Caspian Sea, and to take an exact Observation of the Latitude, &c. of the Coasts, have reported since their Return, that when they went ashore and were got 150 Leagues to the N. E., they found a great Stone Building above half covered with Sand, the Architecture of which, was almost like the Ruins of Ancient Persepolis; and at entering it, they found Presses of a black hard sort of Wood, containing near 3000 Volumes in large Quartos, whose Leaves were the 14th part of an Inch thick, and blue, and the Characters white.

They add that they intended to have brought the said Library along with them, but that the Superstitious People of the Country opposed it, for fear that the Structure which they look upon as a sacred Monument, should be profaned by their suffering anything to be carried out of it. Nevertheless the Muscovite Travellers found means to convey away 3 Volumes, and have brought them to this City, but there’s nobody wise enough here to Decypher the Characters; for which reason the Czar has caused exact Copies of the first Pages of the said Books to be drawn out, and…